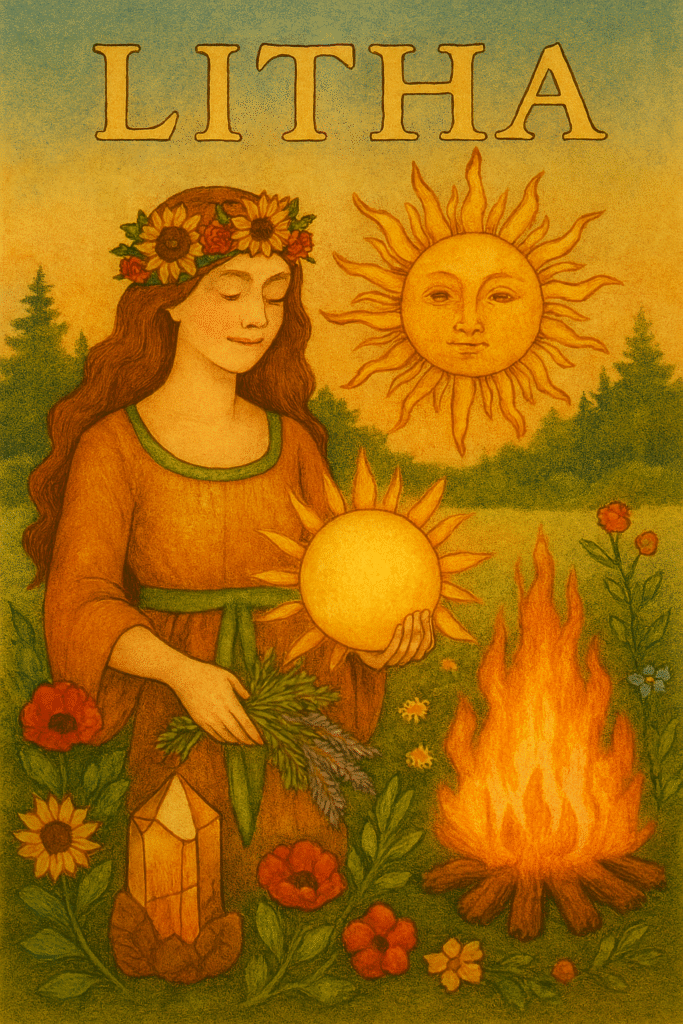

Litha, also known as Midsummer or the Summer Solstice, marks the longest day and shortest night of the year, typically falling between 20–23 June in the Northern Hemisphere. Rooted in ancient solar worship and agrarian cycles, Litha is a time of radiant abundance, honouring the power of the sun at its zenith and the turning of the seasonal wheel toward harvest and decline.

Historical Origins

The origins of Litha can be traced to pre-Christian solstice celebrations across Europe. In Anglo-Saxon England, the term “Litha” referred to the months of June and July, as recorded by the Venerable Bede. Germanic, Celtic, and Norse cultures all observed midsummer rites, often involving bonfires, feasting, and fertility rituals.

- Celtic Traditions: Though Litha is not one of the four major Celtic fire festivals, it was nonetheless observed with reverence. Druids are believed to have gathered at stone circles such as Stonehenge to mark the solstice sunrise.

- Norse Influence: In Scandinavian regions, Midsummer was celebrated with maypole dancing, flower crowns, and offerings to nature spirits.

- Slavic Rites: Kupala Night, a Slavic solstice festival, involved fire-jumping, water rituals, and the search for the mythical fern flower—said to bloom only on this night and grant insight or hidden knowledge.

Folklore and Symbolism

Litha is steeped in solar mythology. The Oak King, who reigns from Yule to Litha, is said to battle the Holly King at the solstice. Though the Oak King is at the height of his power, he is defeated, and the Holly King begins his ascent, ruling until Yule. This symbolic shift reflects the waning of daylight and the cyclical nature of life, death, and rebirth.

Other folkloric themes include:

- Elemental Balance: Litha represents the peak of fire energy, yet water rituals are often included to temper and balance the heat.

- Fae Activity: Folklore holds that the veil between worlds is thin at Midsummer, and faeries are particularly active. Offerings of milk, honey, and bread were traditionally left at garden edges or sacred groves.

- Sun Deities: Celebrants may honour solar deities such as Lugh (Celtic), Baldur (Norse), Ra (Egyptian), or Amaterasu (Japanese), depending on their spiritual path.

Rituals and Traditions

Modern Pagan and Wiccan observances of Litha vary, but common practices include:

- Bonfires: Central to Litha celebrations, bonfires symbolise the sun’s power and are used for purification, protection, and fertility blessings.

- Sunrise Gatherings: Watching the solstice sunrise, particularly at sacred sites, is a way to honour the solar cycle.

- Herb Harvesting: Herbs gathered at Midsummer—especially St. John’s Wort, mugwort, and vervain—are believed to hold heightened potency.

- Feasting and Dancing: Seasonal foods such as berries, honey cakes, and mead are shared, often accompanied by music and circle dancing.

- Nature Altars: Altars are adorned with sunflowers, oak leaves, golden candles, and symbols of fire and light.

Gift-Giving and Seasonal Offerings

Litha is a time for exchanging gifts that reflect solar energy, growth, and gratitude. Popular items include:

- Crystals: Citrine, sunstone, carnelian, and amber are favoured for their solar resonance and vitality.

- Herbal Bundles: Dried midsummer herbs tied with golden ribbon serve as protective talismans or ritual tools.

- Sun Motifs: Jewellery, wall hangings, or altar pieces featuring sun symbols honour the season’s essence.

- Floral Crowns: Handmade crowns of wildflowers and herbs are worn or gifted as tokens of joy and connection to nature.

- Beeswax Candles: Representing the sun’s golden light, these are often infused with midsummer scents like lavender, rosemary, or citrus.